The Dam Busters (film)

| The Dam Busters | |

|---|---|

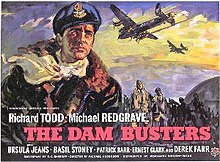

1955 British quad format film poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Anderson |

| Screenplay by | R. C. Sherriff |

| Based on | The Dam Busters by Paul Brickhill Enemy Coast Ahead by Guy Gibson |

| Produced by | Robert Clark W. A. Whittaker |

| Starring | Richard Todd Michael Redgrave |

| Cinematography | Erwin Hillier Gilbert Taylor (Special Effects Photography) |

| Edited by | Richard Best |

| Music by | Eric Coates Leighton Lucas |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Associated British Pathé |

Release date |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | £419,528 (UK)[1] |

The Dam Busters is a 1955 British epic docudrama war film starring Richard Todd and Michael Redgrave, that was directed by Michael Anderson. Adapted by R. C. Sherriff from the the books The Dam Busters (1951) by Paul Brickhill and Enemy Coast Ahead (1946) by Guy Gibson, the film depicts the true story of Operation Chastise when in 1943 the RAF's 617 Squadron attacked the Möhne, Eder, and Sorpe dams in Nazi Germany with Barnes Wallis's bouncing bomb.

The Dam Busters was acclaimed by critics, who widely praised its acting (especially Todd and Redgrave's), Anderson's direction, its superlative special effects photography by Gilbert Taylor and soundtrack score by Eric Coates (especially the stirring The Dam Busters March theme tune). The film was Britain's biggest box-office success of 1955.[2] A much-loved British classic, The Dam Busters has since been cited as one of the best British war films and one of the greatest films of the 20th century. In 1999, the British Film Institute voted The Dam Busters the 68th greatest British film of the 20th century.[3] Its depiction of the raid, along with a similar sequence in the film 633 Squadron, provided the inspiration for the Death Star trench run in Star Wars.

A remake has been in development since 2008, but has yet to be produced as of 2024[update].

Plot[edit]

The film is divided into two distinct sections. In the first and longest of the two, aeronautical engineer Barnes Wallis is struggling to develop a means of attacking Germany's dams in the hope of crippling German heavy industry. Working for the Ministry of Aircraft Production, as well as his own job at Vickers, he works feverishly to make practical his theory of a bouncing bomb which would skip over the water to avoid protective torpedo nets. When it hit the dam, backspin would make it sink whilst retaining contact with the wall, making the explosion far more destructive. Wallis calculates that the aircraft will have to fly extremely low (150 feet (46 m)) to enable the bombs to skip over the water correctly, but when he takes his conclusions to the Ministry, he is told that lack of production capacity means they cannot go ahead with his proposals. Frustrated, Wallis secures an interview with Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris, the head of RAF Bomber Command, who at first is reluctant to take the idea seriously. Eventually, however, he is convinced and takes the idea to the Prime Minister, who authorises the project.

Bomber Command forms a special squadron of Lancaster bombers, 617 Squadron, to be commanded by Wing Commander Guy Gibson, and tasked to fly the mission. He recruits experienced crews, especially those with low-altitude flight experience. While they train for the mission, Wallis continues his development of the bomb but has problems, such as the bomb breaking apart upon hitting the water. This requires the drop altitude to be reduced to 60 feet (18 m). With only a few weeks to go, and despite the fraught, he is ultimately successful in fixing the problems as the dateline for the mission approaches.

In the second and pacier section, the bombers attack the Ruhr Dams. Eight Lancasters and their crews are lost, but the Möhne and Edersee dams are breached, causing catastrophic flooding. Wallis is deeply affected by the loss of the crewmen, but Gibson stresses the squadron knew the risks they were facing but they went in regardless. Wallis asks if Gibson will get some sleep; Gibson says that he has to write letters first to the dead airmen's next of kin.

Cast[edit]

In credits order.

- Richard Todd as Wing Commander Guy Gibson, CO of 617 Squadron and pilot of "George"

- Michael Redgrave as Barnes Wallis, assistant chief designer, Aviation Section, Vickers-Armstrong Ltd

- Ursula Jeans as Mrs Molly Wallis

- Basil Sydney as Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, GOC-in-C, RAF Bomber Command

- Patrick Barr as Captain Joseph "Mutt" Summers, Chief Test Pilot, Vickers-Armstrong Ltd

- Ernest Clark as Air Vice-Marshal Ralph Cochrane, AOC, No. 5 Group RAF

- Derek Farr as Group Captain John Whitworth, station commander, RAF Scampton

- Charles Carson as Doctor

- Stanley Van Beers as David Pye, director of scientific research, Air Ministry

- Colin Tapley as Dr William Glanville, director of Road Research, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research

- Frederick Leister as committee member

- Eric Messiter as committee member

- Laidman Browne as committee member

- Raymond Huntley as National Physical Laboratory Official

- Hugh Manning as Ministry of Aircraft Production Official

- Edwin Styles as Observer at Trials

- Hugh Moxey as Observer at Trials

- Anthony Shaw as RAF Officer at Trials

- Laurence Naismith as Farmer

- Harold Siddons as Group Signals Officer

- Frank Phillips as BBC Announcer

- Brewster Mason as Flight Lieutenant Richard Trevor-Roper, rear gunner of "George"

- Anthony Doonan as Flight Lieutenant Robert Hutchison, wireless operator of "George"

- Nigel Stock as Flying Officer Frederick Spafford, bomb aimer of "George"

- Brian Nissen as Flight Lieutenant Torger Taerum, navigator of "George"

- Robert Shaw as Flight Sergeant John Pulford, flight engineer of "George"

- Peter Assinder as Pilot Officer Andrew Deering, front gunner of "George"

- Richard Leech as Squadron Leader Melvin "Dinghy" Young, pilot of "Apple"

- Richard Thorp as Squadron Leader Henry Maudslay, pilot of "Zebra"

- John Fraser as Flight Lieutenant John Hopgood, pilot of "Mother"

- David Morrell as Flight Lieutenant Bill Astell, pilot of "Baker"

- Bill Kerr as Flight Lieutenant H. B. "Micky" Martin, pilot of "Popsie"

- George Baker as Flight Lieutenant David Maltby, pilot of "Johnny"

- Ronald Wilson as Flight Lieutenant Dave Shannon, pilot of "Leather"

- Denys Graham as Flying Officer Les Knight, pilot of "Nancy"

- Basil Appleby as Flight Lieutenant Bob Hay, bomb aimer of "Popsie"

- Tim Turner as Flight Lieutenant Jack Leggo, navigator of "Popsie"

- Ewen Solon as Flight Sergeant G. E. Powell, crew chief

- Harold Goodwin as Gibson's batman

- Peter Arne (uncredited) as Staff Officer to Air-Vice Marshal Cochrane

- Edward Cast (uncredited) as Crew Member

- Richard Coleman (uncredited) as RAF Officer

- Brenda de Banzie (uncredited) as Waitress

- Peter Diamond (uncredited) as Tail Gunner

- Gerald Harper (uncredited) as RAF Officer

- Arthur Howard (uncredited) as RAF Pay Clerk in NAAFI

- Lloyd Lamble (uncredited) as Collins

- Philip Latham (uncredited) as Flight Sergeant

- Patrick McGoohan (uncredited) as RAF Security Guard [N 1]

- Edwin Richfield (uncredited) as RAF Officer

Cast notes:

- Elisabeth Gaunt, Barnes Wallis's daughter in real life, appears as a photographer in the test tank[4]

- The film featured several actors who would go on to be stars of cinema and TV. Robert Shaw was featured as Gibson's engineer Flt Sgt Pulford.[5] Anderson was struggling to find an actor who psychically resembled Pulford until he went to launch with Redgrave and Shaw, who was one of his theatre friends; Anderson was impressed by the resemblance and Redgrave confirmed to Anderson that Shaw was an actor. The film was Shaw's first major film role. George Baker played Flt Lt Maltby.[6] Charles Foster, nephew of Dambuster pilot David Maltby, said his family formed a bond with Baker. Patrick McGoohan had a bit part as a security guard,[7] standing guard outside the briefing room. He delivered the line—"Sorry, old boy, it's secret—you can't go in. Now, c'mon, hop it!", which was cut from some prints of the film.[citation needed] McGoohan and Nigel Stock, a co-star in the film, both played Number Six in The Prisoner (1967–1968). Richard Thorp played Sqn Ldr Maudslay.[8]

Development[edit]

Director Howard Hawks had wanted to make a film about the raid and had hired Roald Dahl to write the script. Bomber command and Barnes Wallis were reluctant to reveal secrets to a Hollywood studio and the script was disliked by them. By the late 1940s, rumours were that Hollywood were developing a project on the Dam Busters raid and Sir Michael Balcon was in discussion to make a film of the raid with Earling studios; neither project came to fuition., Following the success of the 1951 book The Dam Busters (a RAF-approved history of 617 Squadron), Robert Clark the head of production at Associated British Picture Corporation (ABPC) approached its author Paul Brickhill about acquiring the film rights as a vehicle for Richard Todd. The company's production manager was, however, of the opinion that, due to its numerous personnel and raids, it would not be able to film the book in its entirety. As a result, Clark requested that Brickhill provide a film treatment which described his vision for the film. Brickhill agreed to do it without payment in the hope of selling the film rights. To assist him, Clark teamed him up with Walter Mycroft who was the company's director of production.[9] Brickhill decided to concentrate the film treatment on Operation Chastise and ignore the later raids. The film also took inspiration from the account Enemy Coast Ahead by Guy Gibson.

After the Air Ministry agreed to make available four Lancaster bombers at a cheap price which helped make the production viable, Associated British decided to proceed with the film and agreed with Brickhill on the film rights in December 1952 for what is believed to have been £5,000.[10] After considering C.S. Forester, Terence Rattigan, as well as Emlyn Williams and Leslie Arliss, R. C. Sherriff was selected as the screenwriter with planned August delivery of the screenplay.[11] Sherriff agreed with Brickhill's opinion that the film needed to concentrate on Operation Chastise and exclude the later operations covered in the book.

In preparation for writing the script, Sherriff met with Barnes Wallis at his home, later returning accompanied by Brickhill, Walter Mycroft and production supervisor W.A. "Bill" Whittaker on 22 March 1952 to witness Wallis demonstrating his original home experiment. To Wallis's embarrassment he couldn't get it to work, no matter how many times he tried.[12]

Just prior to the film's scheduled release, Guy Gibson's widow Eve took legal action to prevent it, and Brickhill and Clark were mired in months of wrangling with her until references to her husband's book Enemy Coast Ahead were included.

Real life participants advised Anderson on the events; the RAF gave their blessing to the production and Group Captain Charles Whitworth became technical advisor and gave Anderson all the support he needed. Barnes Wallis read the script too and gave his full approval, wanting to ensure the film was as accurate as possible. Anderson casted actors who resembled their real life counterparts. Richard Todd had a striking physical resemblance to Guy Gibson. Makeup was used to make Michael Redgrave resemble Barnes Wallis.[13] Baker stated that he was chosen for the part due to his physical similarity to Maltby.[14]

Production[edit]

Anderson made the choice to shoot the film in black and white to allow the integration of original footage of the bomb trails, to boast a "gritty" documentary-style reality.

The flight sequences of the film were shot using real Avro Lancaster bombers supplied by the RAF. The aircraft, four of the final production B.VIIs, had to be taken out of storage and specially modified by removing the mid-upper gun turrets to mimic 617 Squadron's special aircraft, and cost £130 per hour to run, which amounted to a tenth of the film's costs. A number of Avro Lincoln bombers were also used as "set dressing".[15] (An American cut was made more dramatic by depicting an aircraft flying into a hill and exploding. This version used stock footage from Warner Brothers of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, not a Lancaster.)

The Upper Derwent Valley in Derbyshire (the test area for the real raids) doubled as the Ruhr valley for the film.[16] The scene where the Dutch coast is crossed was filmed between Boston, Lincolnshire, and King's Lynn, Norfolk, and other coastal scenes near Skegness. The scene where they fly along a canal was filmed on the Dutch river (local nickname for the canal) on the way to Goole which is on the M62 to Hull. As the planes turn across country you can see Goole fully as they turn. This was used as the area around Goole is perfectly flat. Additional aerial footage was shot above Windermere, in the Lake District.

While RAF Scampton, where the real raid launched, was used for some scenes, the principal airfield used for ground location shooting was RAF Hemswell, a few miles north and still an operational RAF station at the time of filming. Guy Gibson had been based at Hemswell in his final posting and the airfield had been an operational Avro Lancaster base during the war. At the time filming took place it was then home to No. 109 Squadron and No. 139 Squadron RAF, which were both operating English Electric Canberras on electronic countermeasures and nuclear air sampling missions over hydrogen bomb test sites in the Pacific and Australia. However, part of the RAF's fleet of ageing Avro Lincolns had been mothballed at Hemswell prior to being broken up and several of these static aircraft appeared in background shots during filming, doubling for additional No 617 Squadron Lancasters. The station headquarters building still stands on what is now an industrial estate and is named Gibson House. The four wartime hangars also still stand, little changed in external appearance since the war.[17]

Serving RAF pilots from both squadrons based at Hemswell took turns flying the Lancasters during filming and found the close formation and low level flying around Derwentwater and Windermere exhilarating and a welcome change from their normal high level solo Canberra sorties. While filming on one of the first days with the Lancasters, a Lancaster's tail wheel caught the roof of a nearby hanger, to the chagrin of an control tower officer.

Three of the four Lancaster bombers used in the film had also appeared in the Dirk Bogarde film Appointment in London two years earlier.[18]

The theatre scene showing the spotlights was filmed at the Lyric Theatre Hammersmith. The dance troupe was The Television Toppers, on loan for one day filming, under contract from the BBC. The singer was June Powell,[19] she sings the 1942 song "Sing Everybody Sing" by John P Long.[20]

Richard Todd described filming the final scene with Michael Redgrave, where Gibson says he has to write letters, saying that as he walked away from the camera he was quietly weeping. He had his own experience of letter writing. He also said that the dog, also named Nigger, refused to go near the spot where the real Nigger was buried.[21]

Soundtrack[edit]

The Dam Busters March, by Eric Coates, is for many synonymous with the film, as well as with the exploit itself, and remains a favourite military band item at flypasts and in the concert hall.[citation needed]

Other than the introduction and trio section theme, the majority of the march as performed is not featured in the film soundtrack. Coates himself avoided writing music for the cinema, remembering the experiences of his fellow composer Arthur Bliss.[22] Coates only agreed to provide an overture for the film after he was persuaded by the film's producers it was of "national importance" and pressure was put on him via his publisher, Chappell. A march he had recently completed was found to fit well with the heroic subject and was thus submitted.[23] The majority of the soundtrack including the theme played during the raid sequence in the film was composed by Leighton Lucas.

Philip Lane, who reconstructed parts of Leighton Lucas's orchestral score (which had been lost) notes that Lucas created his own main theme "which seems to play hide and seek with Coates's throughout the film, both vying for supremacy."[24]

Historical accuracy[edit]

The film is largely historically accurate, with only a small number of changes made for reasons of dramatic licence. Some errors derive from Paul Brickhill's book, which was written when much detail about the raid was not yet in the public domain.

- Barnes Wallis said that he never encountered any opposition from bureaucracy. In the film, when a reluctant official asks what he can possibly say to the RAF to persuade them to lend a Vickers Wellington bomber for flight testing the bomb, Wallis suggests: "Well, if you told them that I designed it, do you think that might help?" Barnes Wallis was heavily involved with the design of the Wellington, as it used his geodetic airframe construction method, though he was not actually its chief designer.

- Instead of all of Gibson's tour-expired crew at 106 Squadron volunteering to follow him to his new command, only his wireless operator, Hutchinson, went with him to 617 Squadron.

- Rather than the purpose as well as the method of the raid being Wallis's sole idea, the dams had already been identified as an important target by the Air Ministry before the war.

- Gibson did not devise the spotlights altimeter after visiting a theatre; it was suggested by Benjamin Lockspeiser of the Ministry of Aircraft Production after Gibson requested they solve the problem. It was a proven method used by RAF Coastal Command aircraft for some time.[25]

- The wooden "coat hanger" bomb sight intended to enable crews to release the weapon at the right distance from the target was not wholly successful; some crews used it, but others came up with their own solutions, such as pieces of string in the bomb-aimer's position and/or markings on the blister.

- Nigger is depicted being killed on the day of raid; it actually happened the day before.[26]

- No bomber flew into a hillside near a target on the actual raid. This scene, which is not in the original version, was included in the copy released on the North American market (see above). Three bombers are brought down by enemy fire and two crashed due to hitting power lines in the valleys.[27]

- Some of the sequences showing the testing of Upkeep—the code name for the weapon—in the film are of Mosquito fighter-bombers dropping the naval version of the bouncing bomb, code-named Highball, intended to be used against ships. This version of the weapon was never used operationally.

- At the time the film was made, certain aspects of Upkeep were still held classified, so the actual test footage was censored to hide any details of the test bombs (a black dot was superimposed over the bomb on each frame), and the dummy bombs carried by the Lancasters were almost spherical but with flat sides rather than the true cylindrical shape.

- The dummy bomb did not show the mechanism which created the back spin.

- Ammunition shown being loaded into a Lancaster is .50 calibre for M2 Browning heavy machine guns, not that for the .303 calibre machine guns found on the Lancaster in 1943.

- The scenes of the attack on the Eder Dam show a castle resembling Schloss Waldeck on the wrong side of the lake and dam. The position and angle of the lake in relation to the castle suggest that in reality the bombing-run would have needed a downhill approach to the west of the castle.

- Wallis states that his idea came from Nelson's bouncing cannonballs into the sides of enemy ships. (He also states that Nelson sank one ship during the Battle of the Nile with a yorker, a cricket term for a ball that bounces under the bat, making it difficult to play.) There is no evidence for this claim. In a 1942 paper, Wallis mentioned the bouncing of cannonballs in the 16th and 17th centuries, but Nelson was not mentioned.[28]

- In the film Wallis (Redgrave) tells Gibson and Young that a mechanical problem with the release gear has been solved as the engineers had the correct oil in store. This is false; there was a technical problem which was solved by Sgt Charles Sackville-Bryant, who was awarded the BEM for this.[citation needed]

Release[edit]

The Dambusters received a Royal world premiere at the Empire, Leicester Square on 16 May 1955, the twelfth anniversary of the raid.[29] Princess Margaret attended along with Eve Gibson, Guy Gibson's widow and his father. Richard Todd, Barnes Wallis and his wife and the surviving members of 617 Squadron who had taken part in the mission were all guests of honour. The premiere helped to raise money and awareness for various RAF charities.[30]

The film was first shown on British television on 30 May 1971.[31]

Reception[edit]

Critical[edit]

Reviews upon its release were positive. Variety described the film as having great attention to detail.[32]

Over time, the film's reputation has grown and is now regarded as a beloved classic of British cinema.[33] The British Film Institute placed The Dam Busters as the 68th greatest British film. In 2004, the magazine Total Film named The Dam Busters the 43rd greatest British film of all time. In a 2015 review, The Guardian stated that The Dam Busters remains very well made and entertaining.[34] The film holds a 100% rating with an average rating of 7.9/10 on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 11 reviews.[35] David Parkinson of Empire gave the film three out of five, describing the film as "patriotic and spirit-lifting".[36] A review commented, "It is testament to Anderson's authoritative, quiet guidance that the performances are largely realistic, and multi-dimensional."[37]

Richard Todd considered the film as one of his favourites of all those that he appeared in, and went on to appear at many Dambusters themed events.[38]

Awards[edit]

The film was nominated for an Oscar for Best Special Effects,[39] and was also nominated for BAFTA awards for Best British Film, Best Screenplay and Best Film From Any Source.[40]

Box office[edit]

The film was the most successful film at the British box office in 1955[41][42] but performed poorly at the US box office, like most British war movies of this era.[43]

Legacy[edit]

Director George Lucas hired Gilbert Taylor, responsible for special effects photography on The Dam Busters, to be the director of photography for the film Star Wars.[44] The attack on the Death Star in the climax of Star Wars is a deliberate and acknowledged homage to the climactic sequence of The Dam Busters. In the former film, rebel pilots have to fly through a trench while evading enemy fire and fire a proton torpedo at a precise distance from the target to destroy the entire base with a single explosion; if one run fails, another run must be made by a different pilot. In addition to the similarity of the scenes, some of the dialogue is nearly identical. Star Wars also ends with an Elgarian march, like The Dam Busters.[45] The same may be said of 633 Squadron, in which a squadron of de Havilland Mosquitos must drop a bomb on a rock overhanging a key German factory at the end of a Norwegian fjord.[46]

On 16 May 2008, a commemoration of the 65th anniversary was held at Derwent Reservoir, including a flypast by a Lancaster, Spitfire, and Hurricane. The event was attended by actor Richard Todd, representing the film crew and Les Munro, the last surviving pilot from the original raid, as well as Mary Stopes-Roe, the elder daughter of Sir Barnes Wallis.

On 17 May 2018, a commemoration of the 75th anniversary was held, in which a restored version of the film was broadcast live from the Royal Albert Hall, and hosted by Dan Snow. The film was simulcast into over 300 cinemas nationwide.[47]

Censorship[edit]

Gibson's black Labrador, Nigger, whose name was used as a single codeword whose transmission conveyed that the Möhne Dam had been breached, is portrayed in several scenes; his name and the codeword are mentioned fourteen times. Some of these scenes were sampled in the film Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982).[48]

In 1999, British television network ITV broadcast a censored version of the film, removing all utterances of "Nigger". ITV blamed regional broadcaster London Weekend Television, which in turn alleged that a junior staff member had been responsible for the unauthorised cuts. When ITV again showed a censored version in June 2001, it was condemned by the Index on Censorship as "unnecessary and ridiculous" and because the edits introduced continuity errors.[49] The code word "nigger" transmitted in Morse code upon the successful completion of the central mission was not censored.

Some edited American versions of the film have used dubbing to change Nigger's name to "Trigger". The British Channel 4 screened a censored American version in July 2007, this screening took place just after the planned remake was announced. In September 2007, as part of the BBC Summer of British Film series, The Dam Busters was shown at selected cinemas across the UK in its uncut format. In 2012, ITV3 showed the film uncut a few times, but with a warning at the start that it contains racial terms from the period which some people may find offensive. The original, uncensored, version was also shown on 1 and 5 January 2013, by Channel 5 without any warning. It was the version, distributed by StudioCanal, containing shots of the bomber flying into a hill. On 17 May 2018, an uncut version was shown on the UK channel Film4 with a warning explaining the film was historical and that some would find it to be racially offensive; "While we acknowledge some of the language used in The Dam Busters reflects historical attitudes which audiences may find offensive, for reasons of historical accuracy we have opted to present the film as it was originally screened". The film was also shown uncut in cinemas.[50][51][52]

Since 2020, following the George Floyd protests in the United Kingdom, Film 4 has broadcast an edited version, re-dubbed in a few places, where the dog's name is removed, addressed as "old boy" or referred to as "my dog", although the warning is retained at the start.

In his book, journalist Sir Max Hastings said that he was repeatedly asked whether it is an embarrassment to acknowledge Nigger's name, and stated that "a historian's answer must be: no more than the fact that our ancestors hanged sheep-stealers, executed military deserters and imprisoned homosexuals. They did and said things differently then. It would be grotesque to omit Nigger from a factual narrative merely because the word is rightly repugnant to twenty-first-century ears."[53]

Planned remake[edit]

Work on a remake of The Dam Busters, produced by Peter Jackson and directed by Christian Rivers, began in 2008, based around a screenplay by Stephen Fry. Jackson said in the mid-1990s that he became interested in remaking the 1955 film, but found that the rights had been bought by Mel Gibson. In 2004, Jackson was contacted by his agent, who said Gibson had dropped the rights. In 2005, the rights were purchased by Sir David Frost, from the Brickhill family.[54] Stephen Fry wrote the script.[55]

In 2007, it was announced it would be distributed by Universal Pictures in North America, and StudioCanal, the corporate heir to ABPC, in the rest of the world.[56] Filming was planned to commence in 2009, on a budget of US$40 million,[57] although no project-specific filming began.[58] The project was delayed because Jackson decided to make The Hobbit.

Weta Workshop was making the models and special effects for the film and had made 10 life-size Lancaster bombers.[59] Fry said Wing Commander Guy Gibson's dog "Nigger" will be called "Digger" in the remake to avoid rekindled controversy over the original name.[60] For the remake, Peter Jackson has said no decision has been made on the dog's name, but is in a "no-win, damned-if-you-do-and-damned-if-you-don't scenario", as changing the name could be seen as too much political correctness, while not changing the name could offend people.[61] Further, executive producer Sir David Frost was quoted in The Independent as stating: "Guy sometimes used to call his dog Nigsy, so I think that's what we will call it. Stephen has been coming up with other names, but this is the one I want."[62][N 2] Les Munro, a pilot in the strike team, joined the production crew in Masterton as technical advisor. Jackson was also to use newly declassified War Office documents to ensure the authenticity of the film.[64]

After Munro died in 2015, Phil Bonner of the Lincolnshire Aviation Heritage Centre said he still thought Jackson will eventually make the film, citing Jackson's passion for aviation. Jackson said, "There is only a limited span I can abide, of people driving me nuts asking me when I'm going to do that project. So I'll have to do it. I want to, actually, it's one of the truly great true stories of the Second World War, a wonderful, wonderful story."[65]

In 2018, news emerged that Jackson was to begin production on the film once again. He intended for production to commence soon, as he only had the film rights for "another year or two".[66]

In popular culture[edit]

- In the 1982 film Pink Floyd The Wall, scenes from The Dam Busters can be seen and heard playing on a television set several times during the film. Particular emphasis is placed on scenes in the film where characters mention Nigger, Guy Gibson's Labrador. "The reason that The Dam Busters is in the film version of The Wall," explained the Floyd's Roger Waters, "is because I'm from that generation who grew up in postwar Britain, and all those movies were very important to us. The Dam Busters was my favourite of all of them. It's so stuffed with great characters."[67] Waters had previously introduced the band's song 'Echoes' at live shows as 'March of the Dam Busters'.

- The 1973 film The Goodies and the Beanstalk incorporates a scene where the eponymous heroes take cover and are attacked by geese dropping golden eggs. To the Dambusters March tune, one of the eggs bounces several times before exploding against the wall behind which they have hidden.

- The 1984 video game The Dam Busters was partially based on the film.

- Two television advertisements were made for a brand of beer, Carling Black Label, which played on the theme of The Dam Busters. Both were made before the English football team broke a 35-year losing streak against Germany. The first showed a German guard on top of a dam catching a number of bouncing bombs as if he were a goalkeeper. The second showed a British tourist throwing a Union Flag towel which skipped off the water like a bouncing bomb to reserve a pool-side seat before the German tourists could reserve them with their towels. Both actions were followed by the comment "I bet he drinks Carling Black Label".[68] The adverts were criticised by the Independent Television Commission, although UK newspaper The Independent reported "a spokeswoman for the German embassy in London dismissed the idea that Germans might find the commercial offensive, adding: 'I find it very amusing'".[69]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ This was McGoohan's feature film debut, playing a guard posted outside a briefing room where the crews are being told of their mission. His only lines are spoken to Gibson's dog.

- ^ Stephen Fry, the screenwriter, said there was "no question in America that you could ever have a dog called the N-word". In the remake, the dog will be called "Digger".[63]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Porter, Vincent. "The Robert Clark Account." Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol. 20, No 4, 2000.

- ^ "R.A.F. Dam Busters of 1943". The Age. No. 30, 935. Victoria, Australia. 26 June 1954. p. 16. Retrieved 3 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ British Film Institute – Top 100 British Films (1999). Retrieved August 27, 2016

- ^ "22/10/2015,". The One Show. BBC. BBC One.

- ^ "Robert Shaw Trivia". 3 June 2010.

- ^ "Chief Inspector Wexford actor George Baker dies aged 80".

- ^ "My Life as a Film: In Profile: Patrick McGoohan". 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Emmerdale star wants dam tribute". BBC News. 23 August 2010.

- ^ Dando-Collins. p. 237.

- ^ Dando-Collins. p. 241.

- ^ Dando-Collins. p. 243.

- ^ Dando-Collins. p. 245.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dqMwNMb-R9Q

- ^ Collin, Robbie (8 October 2011). "George Baker: the man who might have been James Bond". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Garbettt and Goulding 1971, pp. 142–143.

- ^ "Derwent Dam – 617 Dambusters, ladybower dam". Archived from the original on 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Hemswell Airfield History - BCAR.org.uk". www.bcar.org.uk.

- ^ " 'Appointment in London' (film)". imdb.com, 2009. Retrieved: 4 December 2009.

- ^ Forster, Charles (4 October 2017). "Television Toppers under the spotlight". Dambusters Blog. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "Sing Everybody Sing". Dambusters blog. 1 February 2016.

- ^ https://www.key.aero/article/interview-dam-busters-star-richard-todd

- ^ Lace, Ian. "Elgar and Eric Coates". Music Web International. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Cooper, Alan (2013). The Dambusters: 70 Years of 617 Squadron RAF. Pen and Sword. pp. 171–172.

- ^ Lane, Philip (2012). CD notes for "The film music of Arthur Benjamin and Leighton Lucas" (PDF). Chandos Records CH10713. pp. 13–14.

- ^ "National Archives reveals inglorious truth behind classic World War Two movies." culture24.org.uk, 2 September 2009. Retrieved: 23 December 2009.

- ^ Hastings, Max. Operation Chastise: The RAF's Most Brilliant Attack of World War II. HarperCollins, New York, 2020. ISBN 978-0-06-295363-6

- ^ "Bombing Hitler's Dams – NOVA". www.pbs.org.

- ^ Murray, Iain. Bouncing-Bomb Man: The Science of Sir Barnes Wallis. Sparkford, UK: Haynes, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84425-588-7.

- ^ S. P. MacKenzie, Bomber Boys on Screen: RAF Bomber Command in Film and Television Drama, London: Bloomsbury Academic (2019), p. 56.

- ^ Pathé, British. "Dam Busters Royal Premiere". www.britishpathe.com. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ "We delve into The Dam Busters". Dundee Contemporary Arts. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ "The Dam Busters". January 1955.

- ^ Freer, Ian (6 April 2018). "Is this the greatest war film of all time?". The Telegraph.

- ^ Tunzelmann, Alex von (7 August 2015). "The Dam Busters: Hits its targets – and doesn't dumb down". The Guardian.

- ^ "The Dam Busters". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "The Dam Busters".

- ^ http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/483144/index.html British Film Institute Online, accessed 22 May 2024

- ^ "Diamond anniversary of the Dam Busters". Borehamwood Times. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ "The 28th Academy Awards (1956) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences). Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Sir Barnes Wallis – "The Dam Busters"".

- ^ "'The Dam Busters'." Times [London, England], 29 December 1955, p. 12 via The Times Digital Archive. Retrieved: 11 July 2012.

- ^ Thumim, Janet. "The popular cash and culture in the postwar British cinema industry". Screen. Vol. 32, no. 3. p. 259.

- ^ "British War Themes Disappoint". Variety. 8 August 1956. p. 7.

- ^ "Gilbert Taylor BSC". British Cinematographer. 4 May 2015.

- ^ Ramsden, John. "The Dam Busters." google.com. Retrieved: 7 March 2009.

- ^ Kaminski 2007, p. 90.

- ^ "The Dam Busters with Dan Snow to be simulcast from the Royal Albert Hall to cinemas nationwide on 17 May 2018". www.royalalberthall.com. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ "Analysis of the symbols used within the film, "Pink Floyd's The Wall"". Thewallanalysis.com. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ Milmo, Dan. "ITV attacked over Dam Busters censorship." The Guardian, 11 June 2001. Retrieved: 4 December 2009.

- ^ Hilton, Nick (17 May 2018). "Racist name of Dam Busters dog will not be censored in 75th anniversary screenings". The Independent. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "The Dam Busters' dog will still be called the n-word in return to cinemas". inews.co.uk. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "The Dam Busters' return to cinemas to include dog name". guernseypress.com. 16 May 2005. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ Hastings, Max. Operation Chastise: The RAF's Most Brilliant Attack of World War II. HarperCollins, New York, 2020. ISBN 978-0-06-295363-6

- ^ Conlon, Tara. "Frost clears Dam Busters for take-off." guardian.co.uk, 8 December 2005. Retrieved: 4 December 2009.

- ^ Oatts, Joanne. "Fry denies 'Doctor Who' rumours." Digital Spy, 15 March 2007. Retrieved: 21 March 2007.

- ^ "Who you gonna call? The Dam Busters." Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine W Weta Holics. Retrieved: 21 March 2007.

- ^ Cardy, Tom and Andrew Kelly. "Dambusters filming set for next year." The Dominion Post, 1 January 2008. Retrieved: 30 June 2008.

- ^ Katterns, Tanya. "Takeoff Looms For Dam Film." The Dominion Post, 5 May 2009. Retrieved: 4 December 2009.

- ^ "Weta Workshop Vehicles." Archived 6 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine wetanz.com, 2008. Retrieved: 4 December 2009.

- ^ Cardy, Tom. "Dambusters dog bone of contention." stuff.co.nz, 13 June 2011. Retrieved: 20 May 2013.

- ^ Stax. "Jackson Talks Dam Busters." Archived 16 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine IGN, 6 September 2006. Retrieved: 21 March 2007.

- ^ Marks, Kathy. "Nigsy? Trigger? N-word dilemma bounces on for Dam Busters II." The Independent, 6 May 2009. Retrieved: 15 May 2009.

- ^ "Dam Busters dog renamed for movie remake." BBC, 10 June 2011.

- ^ Bromhead, Peter. "Stars bow to hero of missions impossible." nzherald.co.nz, 11 October 2009. Retrieved: 4 December 2009.

- ^ "Will Peter Jackson's remake of The Dam Busters ever get off the ground?". The Independent. 6 August 2015.

- ^ "Peter Jackson says his Dambuster remake will tell "the real story"". The Independent. London. 29 November 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Turner, Steve: "Roger Waters: The Wall in Berlin"; Radio Times, 25 May 1990; reprinted in Classic Rock #148, August 2010, p81

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan. "Bombs away." guardian.co.uk, 6 May 2003. Retrieved: 4 December 2009.

- ^ "Dambuster beer advert leaves a bad taste". The Independent. London. 18 February 1994. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Dando-Collins, Stephen. The Hero Maker: A Biography of Paul Brickhill. Sydney, Australia: Penguin Random House Australia, 2016. ISBN 978-0-85798-812-6.

- Dolan, Edward F. Jr. Hollywood Goes to War. London: Bison Books, 1985. ISBN 0-86124-229-7.

- Garbett, Mike and Brian Goulding. The Lancaster at War. Toronto: Musson Book Company, 1971. ISBN 0-7737-0005-6.

- Kaminski, Michael. The Secret History of Star Wars. Kingston, Ontario, Canada: Legacy Books Press, 2008, First edition 2007. ISBN 978-0-9784652-3-0.

Further reading[edit]

- Ramsden, John. The Dam Busters: A British Film Guide. London: I.B. Tauris & Co., 2003. ISBN 978-1-86064-636-2.

External links[edit]

- The Dam Busters at IMDb

- The Dam Busters at the TCM Movie Database

- The Dam Busters at AllMovie

- May 2003 article in The Guardian revisiting the actual sites of the film, and testifying to the iconic status of The Dam Busters March

- "The Dam-Busters" a 1954 Flight article on the making of the film

- "A Triumphant British Picture" a 1955 Flight review of The Dam Busters film by Bill Gunston

- 1955 films

- 1955 war films

- Operation Chastise

- British aviation films

- British black-and-white films

- British war films

- British World War II films

- Associated British Picture Corporation

- Films about the Royal Air Force

- Films based on multiple works

- Films based on works by Paul Brickhill

- Films directed by Michael Anderson

- Films set in 1943

- Films set in England

- Films set in Lincolnshire

- Films set in Germany

- Films shot at Associated British Studios

- Films shot in Cumbria

- Films shot in Derbyshire

- Films shot in Lincolnshire

- World War II aviation films

- World War II films based on actual events

- 1950s British films

- 1950s English-language films

- Films scored by Eric Coates

- Films scored by Leighton Lucas