Take Off Your Pants and Jacket

| Take Off Your Pants and Jacket | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | June 12, 2001 | |||

| Recorded | December 2000–March 2001[1][2] | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 38:54 | |||

| Label | MCA | |||

| Producer | Jerry Finn | |||

| Blink-182 chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Take Off Your Pants and Jacket | ||||

| ||||

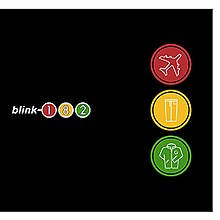

Take Off Your Pants and Jacket is the fourth studio album by American rock band Blink-182, released on June 12, 2001, by MCA Records. The band had spent much of the previous year traveling and supporting their previous album Enema of the State (1999), which launched their mainstream career. The album's title is a tongue-in-cheek pun on male masturbation ("take off your pants and jack it"), and its cover art has icons for each member of the trio: an airplane ("take off"), a pair of pants, and a jacket. It is the band's final release through MCA.

The album was recorded over three months at Signature Sound in San Diego with producer Jerry Finn. During the sessions, MCA executives pressured the band to retain the sound that helped their previous album sell millions. As such, Take Off Your Pants and Jacket continues the pop-punk tone that Blink-182 had honed and made famous, albeit with a heavier post-hardcore sound inspired by bands such as Fugazi and Refused. Regarding its lyrical content, it has been referred to as a concept album chronicling adolescence, with songs dedicated to first dates, fighting authority, and teenage parties. Due to differing opinions on direction, the trio worked in opposition to one another for the first time, and the sessions sometimes became contentious.

The album had near-immediate success, becoming the first punk rock record to debut at number one on the US Billboard 200 and achieving double platinum certification in May 2002. It produced three hit singles—"The Rock Show", "Stay Together for the Kids", and "First Date"—that were top-ten hits on modern rock charts. Critical impressions of the album were generally positive, commending its expansion on teenage themes, although others viewed this as its weakness. To support the album, the band co-headlined the Pop Disaster Tour with Green Day. Take Off Your Pants and Jacket has sold over 14 million copies worldwide.

Background[edit]

At the onset of the millennium, Blink-182 became one of the biggest international rock acts with the release of their third album, the fast-paced, melodic Enema of the State (1999).[3] It became an enormous worldwide success, moving over fifteen million copies.[4] Singles "What's My Age Again?", "All the Small Things", and "Adam's Song" became radio staples, with their music videos and relationship with MTV cementing their stardom.[5][6][7] It marked the beginning of their friendship with producer Jerry Finn, a key architect of their "polished" pop-punk rhythm; according to journalist James Montgomery, writing for MTV News, the veteran engineer "served as an invaluable member of the Blink team: part adviser, part impartial observer, he helped smooth out tensions and hone their multiplatinum sound."[8] The glossy production set Blink-182 apart from the other crossover punk acts of the era, such as Green Day,[9] and this style and sound made for an extensive impact on pop punk, igniting a new wave of the genre.[10]

Behind the scenes, the three were adjusting to this new lifestyle. "After years of hard work, promotion, and nonstop touring, people knew who we were, and listened to what we were saying ... it scared the shit out of us," said bassist Mark Hoppus.[2][11] Each musician was now wealthy and famous, which brought both comfort and challenges: drummer Travis Barker dealt with stalkers at his home.[12] It became a transitionary time for the group, adjusting to larger venues than before, including amphitheaters, arenas, and stadiums. At the beginning of the album's promotional cycle, the trio were driving from show to show in a van with a trailer attached for merchandise and equipment;[13] by its end, they were flying on private jets.[14] Hoppus recalled that "we had gone from playing small clubs and sleeping on people's floors to headlining amphitheaters and staying in five-star hotels."[2] In the public eye, Blink became known for their juvenile antics, including running around nude;[15] the band made a cameo appearance in the similarly bawdy comedy American Pie (1999).[16] While grateful for their success—which the trio parlayed into various business ventures, like Famous Stars and Straps, Atticus Clothing and Macbeth Footwear[17]—they gradually became unhappy with their goofy public image. In one instance, the European arm of UMG had taken photos shot lampooning boy bands and distributed them at face value, making their basis for parody appear thin.[18]

In response, a conscious effort was made to make the trio appear more authentic with their next album. But the relentless pace also was wearing on the group, and the growing divide between art and commerce began to frustrate them. The band was rushed into recording the follow-up, as according to DeLonge, "the president of MCA was penalizing us an obscene amount of money because our record wasn't going to be out in time for them to make their quarterly revenue statements. [...] And we were saying, 'Hey, we can't do this right now, we need to reorganize ourselves and really think about what we want to do and write the best record we can.' They didn't agree with us."[19] To satiate fans in the interim, the band issued a stopgap live album, The Mark, Tom, and Travis Show (The Enema Strikes Back!), which contained more of their high-energy antics, in November 2000.

Recording and production[edit]

Pre-production[edit]

The band began pre-production in December 2000, utilizing ideas they had been developing on the road over the past year.[20] They recorded demos at DML Studios, a small practice studio in Escondido, California, where the band had written Dude Ranch and Enema of the State.[2] The group had written a dozen songs after three weeks and invited their manager, Rick DeVoe, to be the first person outside Blink-182 to hear the new material, which the band found "catchy [but with] a definitive edge".[1][2][21] DeVoe sat in the control room and quietly listened to the recordings, and pressed the band at the end on why there was no "Blink-182 good-time summer anthem [thing]". DeLonge and Hoppus were furious, remarking, "You want a fucking single? I'll write you the cheesiest, catchiest, throwaway fucking summertime single you've ever heard!"[22] Hoppus went home and wrote lead single "The Rock Show" in ten minutes, and DeLonge similarly wrote "First Date", which became the most successful singles from the record and future live staples.[21]

The three worked on the arrangements for those two songs at Barker's Famous Stars and Straps warehouse.[23] Barker also proposed being promoted to official partner in the band; prior to 2001, he had been considered a touring musician only, and while he had arranged the songs on Enema, he received no publishing residuals. Hoppus and Barker obliged—they wanted his input on songwriting.[24] Finn came into the process during the last week of pre-production, and was very fond of Barker's drum parts, which the other musicians found unconventional and "algebraic".[20] Barker remembered going into the process was intimidating but exciting: "We had a lot more pressure on that album than we did before, when nobody seemed to be paying attention. We had this huge success, but that just made us feel like we had something to prove. Instead of saying, 'Let's write some simple songs that will be huge,' we thought we'd try something more technical and darker. We wanted to be taken seriously, and we wanted to challenge ourselves."[24]

Recording[edit]

Take Off Your Pants and Jacket was recorded between December 2000 and March 2001. The band began proper tracking for drums not long after pre-production at Larrabee Studios West and Cello Studios in Hollywood. The working relationship with producer Jerry Finn had been so fruitful that the same team was largely engaged for Take Off Your Pants and Jacket, with Finn producing and Joe McGrath engineering.[25] Barker recorded his drum parts in "two or three days" while DeLonge and Hoppus watched television upstairs.[2] Barker recorded the songs from memory with no scratch tracks, largely in one take;[20] Take Off was the first time he enabled a click track while recording to ensure timing.[26] When the drums were finished, the band returned to San Diego to record the majority of Take Off Your Pants and Jacket at Signature Sound, where they had also recorded its predecessor. While the band worked with few days off, the sessions also proved to be memorable: "We took long dinner breaks, ate Sombrero burritos, watched Family Guy and Mr. Show, and laughed way too hard," said Hoppus.[2] When MCA Records executives traveled to San Diego to hear the highly anticipated follow-up, the trio only played them joke songs—"Fuck a Dog" and "When You Fucked Hitler" (the subject of which later changed to a grandfather)—and the team responded incredulously: "[they] lost it," said DeLonge.[27][28] MCA put pressure on the band to maintain the sound that made Enema of the State sell millions; as a result, DeLonge believed the album took no "creative leaps [or] bounds."[27] As such, DeLonge felt creatively stifled and was privately "bummed out" with the label's limitations.[27][29]

In 2013, Hoppus referred to Take Off Your Pants and Jacket as the "permanent record of a band in transition ... our confused, contentious, brilliant, painful, cathartic leap into the unknown."[2][11] The creative struggle was evident from the outset. Hoppus loved everything regarding Enema of the State—including the music videos and live show—and "wanted to do it again," hoping to create a bigger, better and louder follow-up.[2] DeLonge's guitar style was becoming dirtier and heavier; Arpeggiated guitar hooks became frenetic 1/16th note spasms," observed Hoppus.[2] Meanwhile, drummer Travis Barker's were imbued a sense of hip hop and heavy metal into his technique.[2][11] Hoppus felt his lyricism was largely darker and more introspective: "love songs became broken love songs," he remembrered.[2][11] DeLonge rewrote some of his lyrics after listening to songs by Alkaline Trio, feeling as though he needed to elevate himself.[30] Hoppus remembered that it was the first time the three had worked in opposition to one another, and noted that the sessions sometimes prompted arguments.[11][31] He felt that the sessions created an unspoken competition between him and DeLonge, between who could write the superior lyrics: "Our confidence and insecurity begat some heated differences, sometime to the point where we had to leave rooms and cool down," he said in 2013.[2] Finn helped to resolve these situations by offering fresh insights and good humor.[2]

The band wrote two more songs in the studio; for these songs, Barker looped and filtered his parts and recorded the live drums after the fact.[20] One of these songs became the single "Stay Together for the Kids", which was developed only one day before the album was turned over for mixing.[24]

Technical[edit]

The engineering and post-production team behind Jacket remains largely unchanged from its predecessor. Finn and McGrath, exacting in acquiring the best sound, took two days to assess microphone placement, different compressors, and shifting EQs before committing Barker's drums to tape.[2] Barker had technician Mike Fasano sit in and complete the drum tuning because he disliked waiting for Finn and his team. [20] It was the last Blink album recorded on analogue tape; their next effort involved the emerging Pro Tools software.[32] On the technical side, all of the vocals were recorded with Blue's Bottle condenser tube microphone.[33] DeLonge augments his guitar setup with chorus pedals, flangers and delays – "just really light, tasteful touches", he felt.[27] Barker used a variety of snare drums in his process, which he tuned tightly to his liking; the album uses brands like Ludwig Coliseum and Brady, and many came from Orange County Drum and Percussion. He liked using different snares to match what he felt the song required. To that end, the team rented a Tama snare called "Big Red" that Guns N' Roses used to make "November Rain".[20]

According an EQ piece published after the album's release, Finn was so meticulous in quality that he A/B tested speaker wire from an independent hi-fi shop.[33] Roger Joseph Manning, Jr. returns to add keyboard parts, while Tom Lord-Alge served as the mixing engineer, which was conducted at Encore Studios in Burbank. He typically worked out of his Miami space, but the band had him mix the album in California instead.[20] The band also returned to work with Brian Gardner at Bernie Grundman Mastering in Hollywood.[2] A writer for EQ magazine profiling Finn was present at the mastering session and characterized the atmosphere as "easygoing, the band was relaxed."[33]

Packaging[edit]

The title is a tongue-in-cheek pun on male masturbation ("take off your pants and jack it"). Previous titles had included If You See Kay (a pun on the spelling of "fuck") and Genital Ben, accompanied by a bear on the cover of the album.[1] Stressed at being at a loss for a name, DeLonge asked guitar tech Larry Palm for suggestions.[1] The album's title was coined by Palm, who was snowboarding on a rainy day. Inside the lodge, Palm was congregating with friends when a young kid walked in completely drenched, to which his mother suggested he "take off [his] pants and jacket."[1] Palm was told by DeLonge that if the band were to use the name, he would "hook him up".[34] Instead, Palm received a letter from manager Rick DeVoe for his contribution, which offered a $500 payout for the name. Palm scoffed at the amount, and filed suit in 2003 with the intellectual property attorney Ralph Loeb, alleging breach of contract and fraud against the band.[34] Palm demanded $20,000; the band eventually settled out of court for $10,000.[34] Journalist Joe Shooman called the title "a glint of sharp intelligence behind the boys' humour as it draws oblique attention to the fact that, latterly, Blink-182 had often been encouraged to get naked in order to promote themselves. It's a very self-aware album title in that context and a portent, perhaps, of what was to come".[25]

The cover has three "Zoso-like"[35] icons for each band member: a jacket, a pair of pants and an airplane. Delonge and Hoppus' symbols became the pants and jacket, respectively, leaving Barker the airplane despite begging his bandmates not to assign him the symbol, citing his fear of flying,[36] but he took it anyway.[24] The record was initially released in three separate configurations, for the first million printings[1]: the "red plane", the "yellow pants" and the "green jacket" editions. Each release contained two separate bonus tracks, ranging from joke tracks to outtakes. The only outward signs to differentiate the three editions were three stickers.[28] The multiple bonus-track versions were only available for a limited time before being replaced by an edition without any bonus tracks.[28] "We just wanted it so one kid would get one song, a different kid will get another song," Hoppus explained.[1]

Composition[edit]

While Take Off Your Pants and Jacket fits squarely within the band's "commercial and conventional"[22] pop-punk mold,[37][38] it quietly introduces disparate elements into the band's sound. It ranges from bracingly fast-paced numbers to slower, more emo-indebted songs.[1] Hoppus felt it was a "darker, harder album that pushed the boundaries of what blink-182 could do."[39] Roger Catlin of the Hartford Courant said the album boasts "tight little anthems, with precision playing, staccato lyrics and sing-along choruses."[40] Joshua Klein from The Washington Post described its familiar "sturdy pop elements — chiming guitars, exciting drums, endearing vocals and ear-catching chord changes."[41]

DeLonge's droning guitar style was influenced by post-hardcore bands Fugazi and Refused.[1] "As Blink grew, I wanted to contribute progressive elements: bring some modernism into the band and change what everyone thought we were capable of," DeLonge said.[42] Part of that stemmed from the band's desire to illustrate they were not a boy band, as they felt had been marketed.[43] Additionally, DeLonge's adenoidal vocal twang, with its "cartoonish California diction", is prominent.[44] Barker's drumming is more technical than before; "Don't Tell Me It's Over" uses an Afro-Cuban bass drum and hi-hat pattern,[45][20] and another song takes the beat from James Brown's "Funky Drummer". One song that developed midway through recording utilized looping for a danceable drum 'n' bass style.[20] Barker used these affectations to differentiate the band from the rest of the pop-punk pack: "Every punk rock band sounds recycled," he confided to Modern Drummer in 2001. "It's the same recycled beats. Believe me, I know where you took that fill from. I'm trying to bring more to the table."[20]

Songs[edit]

I lived, ate, and breathed skateboarding. All I did all day long was skateboard. It was all I cared about. So I didn't notice too much [else going on]. When I got home [one] day, my dad's furniture was gone, my mom was inside crying and everything just erupted at that point. I was 18, sitting in my driveway when it all went down. So I just took everything from that day and put it into a song.

Tom DeLonge on "Stay Together for the Kids"[46][47]

Take Off Your Pants and Jacket has been called a concept album chronicling adolescence and associated feelings.[48] The band did not consider them explicitly teenage songs: "The things that happen to you in high school are the same things that happen your entire life," said Hoppus. "You can fall in love at sixty; you can get rejected at eighty."[47][49] The record begins with "Anthem Part Two", which touches on disenchantment and blames adults for teenage problems.[50] It serves as the opposite of the band's typical "party" image presented to the media, with heavily politically-charged lyrics.[51] Joe Shooman called it a "generational manifesto that exhorts kids to be wary of the system that surrounds them".[51] "Online Songs" was written by Hoppus about "the thoughts that drive you crazy" in the aftermath of a breakup, and is essentially a follow-up to "Josie".[51][52] "First Date" was inspired by DeLonge and then wife Jennifer Jenkins' first date at SeaWorld in San Diego.[21] "I was about 21 at the time and it was an excuse for me to take her somewhere because I wanted to hang out with her," said DeLonge. The track was written as a summary of neurotic teen angst and awkwardness.[21] "Happy Holidays, You Bastard" is a joke track intended to "piss parents off."[52] The fifth track, "Story of a Lonely Guy", concerns heartache and rejection prior to the high school prom.[11][52] The song is downbeat and melancholy, filtered through "tuneful guitar lines reminiscent of the Cure and hefty drum patterns".[51]

The following track, "The Rock Show", is the opposite: an upbeat "effervescent celebration of love, life and music". It was written as a "fast punk-rock love song" in the vein of the Ramones and Screeching Weasel.[53] The song tells the story of two teenagers meeting a rock concert, and, despite failing grades and disapproving parents, falling and staying in love.[46] It was inspired by the band's early days in San Diego's all-ages venue SOMA.[52] The dysfunctional[40]"Stay Together for the Kids" follows and is written about divorce from the point of view of a helpless child.[45] Inspired by DeLonge's parents' divorce, it is one of the band's darker songs.[11][46] "Roller Coaster" was written when Hoppus had a nightmare when he and his wife, Skye, first began dating; the song is about finding something ideal but fearing for its certain departure.[45] "Reckless Abandon" was penned by DeLonge as a reflection on summer memories, including parties, skateboarding and trips to the beach.[52] "Everytime I Look for You" has no specific lyrical basis, according to Hoppus, and "Give Me One Good Reason" was written about punk music and nonconformity in a high school setting.[52] Spin columnist Tim Coffman called it "practically a pop-punk answer to "Come On Eileen" [...] "Many of the great pop-punk songs are about rallying against your parents. No one really talked about what to do once the rebellion was over, though."[54] "Shut Up", a "broken-family snapshot", revisits the territory of youthful woes, described by Shooman as a "fairly familiar rites-of-passage tale" that "adds to general themes of isolation, alienation and moving on to a new place that pervade Take Off Your Pants and Jacket".[49][55] "Please Take Me Home" concludes the standard edition of the album and was written about the consequences of a friendship developing into a relationship.[11][52]

Several bonus tracks follow on separate editions; some continue the teenage theme, while others are joke tracks. Notably, "What Went Wrong" is an acoustic track; while DeLonge felt "staple acoustic songs" were big for groups at the time (such as Green Day's "Good Riddance"), the band wrote all of their songs from their inception on acoustic guitars, and he felt he would rather have "What Went Wrong" in its original form.[45] "You grow up and realize, 'Fuck! Who gives a fuck about punk rock?'" he said. "There are so many great forms of music out there, and you grow beyond wanting to listen to or write something because your parents will hate it."[45] Producer Jerry Finn suggested lyrics for the song after viewing a documentary on the first Soviet nuclear test; in the film, an aged Soviet physicist says of watching the explosion, "There was a loud boom, and then the bomb began fiercely kicking at the world."[45]

Promotion[edit]

To promote Take Off Your Pants and Jacket, MCA Records released three singles, "The Rock Show", "First Date" and "Stay Together for the Kids", all of which were top ten hits on Billboard's Modern Rock Tracks chart. The band recorded a television commercial for the LP, starring Hoppus as a proctologist and Barker as his patient.[56] Blink-182 performed on the Late Show with David Letterman and Late Night with Conan O'Brien in support of Take Off Your Pants and Jacket.[25] The band also appeared in a MADtv sketch, in which the trio stars as misfits in an all-American 1950s family in a parody Leave It to Beaver.[57] The trio also sanctioned a band biography, Tales from Beneath Your Mom (2001), which was written by the trio and Anne Hoppus (sister of Mark Hoppus).[57]

Commercial performance[edit]

Take Off was a marquee rock release of the season,[58] alongside acts like Staind and Tool;[59] writer Jim DeRogatis of the Chicago Sun-Times viewed it an "unlikely modern-rock radio blockbuster in an era otherwise dominated by vapid nu-metal."[60] Like many high profile releases of the era, Take Off Your Pants and Jacket was leaked on the Internet prior to release. The album's leak is mentioned in the book How Music Got Free, which profiles the warez group Rabid Neurosis, as well as the North Carolina CD manufacturing facility from which the album leaked.[61] Its assured success allowed the band, according to Brittany Spanos at Rolling Stone to "fully settle into their status as one of the biggest rock bands in the world."[62] "There's nowhere to go but down," Hoppus joked.[63]

Upon its official June 2001 bow,[64] the album debuted at number one on the US Billboard 200 chart, with first-week sales of 350,000 copies. Billboard attributed the success of the record overall as a result of the success of the first single, "The Rock Show".[65] The album debuted at number one on the Canadian Albums Chart, selling 47,390 copies.[66] It also reached number one on Germany's Top 100 Albums.[67] The album was the first album by a punk rock band to debut at number one in the United States.[2][11] The record shipped enough units to be certified platinum, and it sold through those million copies by August.[68] It was later certified double platinum in May 2002.[69] It had moved three million units worldwide by December.[70] Take Off Your Pants and Jacket is the second-highest selling album in the band's catalogue,[71] and has sold over 14 million copies worldwide.[72]

Critical reception[edit]

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 69/100[73] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AbsolutePunk | 95%[74] |

| AllMusic | |

| Entertainment Weekly | C+[76] |

| Q | (favorable)[77] |

| Robert Christgau | A−[78] |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Slant Magazine | |

| Toronto Sun | (favorable)[80] |

| The Village Voice | (favorable)[64] |

| Rock Hard | 7.5/10[81] |

Critical reception of Take Off Your Pants and Jacket in 2001 was generally positive. Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone was generally the most effusive of the positive reviews, praising the unpretentious attitude of the band: "As they plow in their relatively un-self-conscious way through the emotional hurdles of lust, terror, pain and rage, they reveal more about themselves and their audience than they even intend to, turning adolescent malaise into a friendly joke rather than a spiritual crisis."[55] Darren Ratner of AllMusic felt likewise, writing that the record is "one of their finest works to date, with almost every track sporting a commanding articulation and new-school punk sounds. They've definitely put a big-time notch in the win column".[75] People commended the "adrenaline-laced sonic gems reveling in Blink's patented, potty-mouthed humor, recommended only for adolescents of all ages".[82] British publication Q offered the sentiment that "when they stop arsing around for the sake of it, Blink-182 write some very good pop songs".[77]

The Village Voice called the sound "emo-core ... intercut with elegiac little pauses that align Blink 182 with a branch of punk rock you could trace back through The Replacements and Ramones Leave Home, to the more ethereal of early Who songs".[64] Aaron Scott of Slant Magazine, however, found the sound to be recycled from the band's previous efforts, writing, "Blink shines when they deviate from their formula, but it is awfully rare ... The album seems to be more concerned with maintaining the band's large teenage fanbase than with expanding their overall audience."[79] Joshua Klein from The Washington Post felt it was stagnant, critiquing its formula and "cookie-cutter" approach.[41] Kerrang!'s Ian Fortnam critiqued its lack of risks, its "money-in-the-bank commercialism. [It's] eminently hummable dummy-spitting tantrum rock for the emo generation."[83] Entertainment Weekly felt similarly, with David Browne opining that "the album is angrier and more teeth gnashing than you'd expect. The band work so hard at it, and the music is such processed sounding mainstream rock played fast, that the album becomes a paradox: adolescent energy and rebellion made joyless".[76] British magazine New Musical Express, who heavily criticized the band in their previous efforts, felt no more negative this time, saying "Blink-182 are now indistinguishable from the increasingly tedious 'teenage dirtbag' genre they helped spawn". The magazine continued, "It sounds like all that sanitised, castrated, shrink-wrapped 'new wave' crap that the major US record companies pumped out circa 1981 in their belated attempt to jump on the 'punk' bandwagon."[84]

More recent reviews have subsequently been positive. Music critic Kelefa Sanneh complimented the album in a New Yorker profile: "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket is by turns peppy, sulky, and stupid—Blink-182 at its finest."[85] Website AbsolutePunk, in part of their "Retro Reviews" project in 2011, called Take Off Your Pants and Jacket the band's best effort; reviewer Thomas Nassiff referred to it as "a transitory record for Blink-182, but you can't tell just by listening to it on its own. It's developed and it's full – it feels holistically complete, dick jokes and all".[74] In 2005, the album was ranked number 452 in Rock Hard magazine's book The 500 Greatest Rock & Metal Albums of All Time.[86] in 2021, Stereogum's Grant Sharples felt it improved on its predecessor; "[it's an endearing time capsule [...] replete with refined songwriting and incredibly infectious hooks."[87]

Accolades[edit]

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kerrang! | United Kingdom | The 50 Best Rock Albums of the 2000s[88] | 2016 | 14 |

* denotes an unordered list

Touring[edit]

The Take Off Your Pants and Jacket supporting tour began in April 2001 in Australia and New Zealand.[25] The band returned to the US to promote their new record on the Late Show with David Letterman in June 2001.[25] Afterwards, the band set out on the 2001 Honda Civic Tour with No Motiv, Sum 41, the Ataris, and Bodyjar, for which the trio designed a Honda Civic to promote the company.[89] The band again received criticism for "selling out", but the band argued by way of mitigation that their tickets were consistently offered at lower prices than those of other groups of their stature, and by accepting corporate links they could continue to give fans a good deal.[90] Likewise, the band partnered with Ticketmaster, setting up a special website where fans could purchase pre-sale tickets for each show.[91]

The main headlining tour visited arenas and amphitheaters between July and August 2001, and was supported by New Found Glory,[91] Jimmy Eat World, Alkaline Trio[92] and Midtown. Each show winkingly began with the overture of "Also sprach Zarathustra" and debuted a flaming sign reading "FUCK".[93] The band had initially contacted Eminem in hopes of partnering for a tour, but he was too busy. For Barker, he would have preferred to tour with a stylistically different artist: "If it was my choice, we wouldn't tour with other punk bands," he said in 2001.[20] In December 2001, the trio played at a series of radio-sponsored holiday concerts—which Barker liked because of their variety—and also appeared as presenters at the 2001 Billboard Music Awards in Las Vegas.[94] The band rescheduled European tour dates in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. "After the attacks the world kind of went into freeze mode and we didn't know whether to carry on with things or not ... so we decided we'd rather everyone was safe and play the shows a little later instead," said Hoppus shortly thereafter.[95] In the wake of the tragedy, the band draped an American flag over a set of amplifiers and drummer Barker played on a red, white, and blue drum kit. At one concert, DeLonge invited the crowd to join him in his cheers of "Fuck Osama bin Laden!"[96] The European dates were canceled a second time after DeLonge suffered a herniated disc in his back.[97]

In 2002, the band co-headlined the Pop Disaster Tour with Green Day. The tour was conceived by Blink-182 to echo the famous Monsters of Rock tours; the idea was to have, effectively, a Monsters of Punk tour.[98] The tour, from the band's point of view, had been put together as a show of unity in the face of consistent accusations of rivalry between the two bands, especially in Europe.[99] Instead, Green Day's Tré Cool acknowledged in a Kerrang! interview that they committed to the tour as an opportunity to regain their reputation as a great live band, as they felt their spotlight had faded over the years.[99] "We set out to reclaim our throne as the most incredible live punk band from you know who," said Cool.[100] Cool contended that "we heard they were going to quit the tour because they were getting smoked so badly ... We didn't want them to quit the tour. They're good for filling up the seats up front."[100] Several reviewers were unimpressed with Blink-182's headlining set following Green Day. "Sometimes playing last at a rock show is more a curse than a privilege ... Pity the headliner, for instance, that gets blown off the stage by the band before it. Blink-182 endured that indignity Saturday at the Shoreline Amphitheatre," a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle wrote in 2002.[101]

The band released a second DVD of home videos, live performances and music videos titled The Urethra Chronicles II: Harder Faster Faster Harder in 2002.[102] Likewise, the 2003 film Riding in Vans with Boys follows the Pop Disaster Tour throughout the U.S.[99]

Legacy[edit]

Take Off Your Pants and Jacket arrived at the apex of an early aughts, pre-9/11 moment for youth culture.[104] A 2001 Federal Trade Commission report condemned the entertainment industry for marketing lewd lyrics to American youth, specifically naming Blink-182 as among the most explicit acts.[105][106] It debuted at the peak of a pop-punk moment the band helped foment, a brand of snotty pop-punk popularized with progenitors like Sum 41, Simple Plan and Good Charlotte,[107][108][109] all of whom released seminal albums in 2001–02.[110] Its songs became common on peer-to-peer sites like Kazaa and LimeWire,[111][112] and its sound proved influential: its ubiquity made it a "sonic bible for many millennials" according to Kat Bein of Billboard.[113] Others agreed: “If you're part of a certain twenty-something age bracket, you can recite every chorus [of the album]” replied Zach Schonfeld of The Atlantic.[114] The album was an influence on artists like Avril Lavigne,[103] Mod Sun[115] You Me at Six,[116] Knuckle Puck,[117] and Neck Deep,[118] who covered "Don't Tell Me That It's Over" in 2019.[119]

It also marked a transitionary period in the group, with it the first time the trio began to fracture. Shortly after the album’s release, the 9/11 attacks prompted a pause in the band's schedule, which led DeLonge to explore a slower, more heavy musical style—which became the album Box Car Racer (2002). Blink producer Jerry Finn naturally returned to engineer, and DeLonge, ostensibly trying to avoid paying a session player,[29] invited Barker to record drums—making Hoppus the odd man out. It marked a major rift in their friendship: while DeLonge claimed he was not intentionally omitted, Hoppus nonetheless felt betrayed.[29] "At the end of 2001, it felt like Blink-182 had broken up. It wasn't spoken about, but it felt over", said Hoppus later.[120]

Track listing[edit]

All tracks are written by Mark Hoppus, Tom DeLonge and Travis Barker

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Anthem Part Two" | DeLonge | 3:48 |

| 2. | "Online Songs" | Hoppus | 2:25 |

| 3. | "First Date" | DeLonge | 2:51 |

| 4. | "Happy Holidays, You Bastard" | Hoppus | 0:42 |

| 5. | "Story of a Lonely Guy" | DeLonge | 3:39 |

| 6. | "The Rock Show" | Hoppus | 2:51 |

| 7. | "Stay Together for the Kids" |

| 3:59 |

| 8. | "Roller Coaster" | Hoppus | 2:47 |

| 9. | "Reckless Abandon" | DeLonge | 3:06 |

| 10. | "Everytime I Look for You" | Hoppus | 3:05 |

| 11. | "Give Me One Good Reason" | DeLonge | 3:18 |

| 12. | "Shut Up" | Hoppus | 3:20 |

| 13. | "Please Take Me Home" | DeLonge | 3:05 |

| Total length: | 38:56 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14. | "Time to Break Up" | DeLonge | 3:04 |

| 15. | "Mother's Day" | Hoppus | 1:37 |

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14. | "What Went Wrong" | DeLonge | 3:13 |

| 15. | "Fuck a Dog" |

| 1:25 |

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14. | "Don't Tell Me It's Over" | DeLonge | 2:34 |

| 15. | "When You Fucked Grandpa" | Hoppus | 1:39 |

- Notes

- On the clean version of the album the track "Happy Holidays, You Bastard" is listed as just "Happy Holidays", and is an instrumental with the exception of the very last line, due to nearly every other line containing strong language and/or crude sexual references.

- On the limited edition bonus track versions, "Please Take Me Home" has 182 seconds (roughly 3 minutes) of silence at the end, likely to hide the hidden tracks, which are not listed on the back cover, and also to reference their name.

Personnel[edit]

|

|

Charts[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications[edit]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[156] | Platinum | 70,000^ |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[157] | Gold | 50,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[158] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Germany (BVMI)[159] | Gold | 150,000‡ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[160] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[161] | Gold | 20,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[162] | Platinum | 300,000* |

| United States (RIAA)[69] | 2× Platinum | 2,000,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roger Coletti (2001). "Blink-182: No Jacket Required". MTV News. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Take Off Your Pants and Jacket (2013 Vinyl Reissue) (liner notes). Blink-182. US: Geffen / Universal Music Special Markets. 2013. SRC025/SRC026/SRC027/SRC028.

This reference primarily cites the Mark Hoppus foreword.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) Cite error: The named reference "linernotes1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ James Montgomery (February 9, 2009). "How Did Blink-182 Become So Influential?". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ Adams, Matt (October 11, 2022). "Blink-182 are getting the band back together with a new tour". NPR. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ Edwards, Gavins (August 3, 2000). "The Half Naked Truth About Blink-182". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ "Blink-182 Spoofs Boy Bands With New Video". MTV News. August 11, 1999. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ Hoppus, 2001. p. 98

- ^ Montgomery, James (April 8, 2011). "Blink-182's Mark Hoppus Talks Moving On Without Late Producer Jerry Finn". MTV News. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ Jon Carimanica (September 16, 2011). "Not Quite Gone, A Punk Band Is Coming Back". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ^ Diehl, Matt (April 17, 2007). My So-Called Punk: Green Day, Fall Out Boy, The Distillers, Bad Religion – How Neo-Punk Stage-Dived into the Mainstream. St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-312-33781-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kyle Ryan (October 8, 2013). "Blink-182 took punk to No. 1 for the first time with a masturbation pun". The A.V. Club. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ Barker & Edwards 2015, p. 155.

- ^ Barker & Edwards 2015, p. 122.

- ^ Barker & Edwards 2015, p. 140.

- ^ Willman, Chris (February 25, 2000). "Nude Sensation". Entertainment Weekly. No. 527. ISSN 1049-0434. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ Compton, Michael (January 16, 2022). "American Pie Made Two Blink-182 Mistakes (Despite Their Cameo)". ScreenRant. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ Quihuiz, Ariana (April 18, 2023). "The Members of Blink-182: Where Are They Now?". Peoplemag. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ "Tom DeLonge: "People thought Blink-182 were a boy band"". Radio X. October 11, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ Richard Harrington (June 11, 2004). "Seriously, Blink-182 Is Growing Up". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Waleed Rashidi (August 1, 2001). "Blink-182's Travis Barker: "I'm Not Just a Punk Drummer"!". Modern Drummer. Vol. 25, no. 8. New Jersey: Modern Drummer Publications, Inc. pp. 62–74. ISSN 0194-4533.

- ^ a b c d Nichola Browne (November 20, 2005). "Punk Rock! Nudity! Filthy Sex! Tom DeLonge Looks Back On Blink-182's Greatest Moments". Kerrang!. No. 1083. London: Bauer Media Group. ISSN 0262-6624.

- ^ a b "The 100 Greatest Songs of 2001: Staff Picks". Billboard. April 5, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Greene, Andy (October 11, 2011). "How Blink-182 Stopped Fighting and Overcame Years of Bad Blood". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Barker & Edwards 2015, p. 157–58.

- ^ a b c d e Shooman, 2010. p. 82

- ^ Rick Rubin (February 17, 2024). "Tetragrammaton with Rick Rubin: Travis Barker". Apple Podcasts (Podcast). Tetragrammaton LLC. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Tom DeLonge talks guitar tones, growing up and Blink". Total Guitar. Bath, Somerset: Future Publishing. October 12, 2012. ISSN 1355-5049. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Blink-182 plan four versions of new album". Toronto Sun. Toronto: Sun Media. May 7, 2001. ISSN 0837-3175. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Shooman, 2010. p. 94

- ^ Pinfield, Matt (Interviewer); Hoppus, Mark (Interviewee) (June 2, 2016). Mark Hoppus Talks Fatherhood, Alkaline Trio, and the all-new Blink-182 (Podcast). 2Hours with Matt Pinfield. audioBoom. Archived from the original (mp3) on June 3, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ "'Take Off Your Pants And Jacket': Underneath blink-182's Enticing Invitation". uDiscover Music. June 12, 2023. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Kerrang! Radio: Matt Stocks Meets Mark Hoppus From Blink-182 (Part 2) (Streaming video). Kerrang! Radio/YouTube. October 28, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c David Goggin (September 2001). "Bonazi Beat: Jerry Finn, Topping the Charts with Green Day and Blink-182". EQ.

- ^ a b c Ken Leighton (September 14, 2011). "Naming Rights". San Diego Reader. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Edwards, Gavin (August 20, 2009). "Blink-182: Survival of the Snottiest". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Scancarelli, Derek (October 29, 2015). "No Regrets, Only Lessons Learned: Travis Barker on Planes, Pills, and Prophecy". VICE. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Kyle Ryan (October 8, 2013). "Blink-182 took punk to No. 1 for the first time with a masturbation pun". The A.V. Club. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

The history of the Billboard Top 200 is riddled with questionably titled albums, but in 2001, Blink-182 set a new standard. The top album in the country—a first for a punk record—was a masturbation pun.

- ^ Evelyn Lau (October 14, 2022). "All of Blink-182's albums ranked, from 'Dude Ranch' to 'California'". The National News. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

The anticipated follow-up to 1999's Enema of the State did not disappoint as Take Off Your Pants and Jacket became the first punk rock record to reach No 1 on the Billboard 200 on its debut.

- ^ "Blink-182 Celebrate 20th Anniversary of 'Take Off Your Pants and Jacket'". iHeart. June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "Blink-182 Buckles Down On `Take Off Your Pants'". articles.courant.com. June 14, 2001. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b Klein, Joshua (June 20, 2001). "Lite Salad Days With Blink-182". Washington Post. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Barker & Edwards 2015, p. 164.

- ^ Barker & Edwards 2015, p. 378.

- ^ Gray, Julia (November 9, 2023). "I Miss the Tom DeLonge Twang". Vulture. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Heller, Greg (June 2001). "All the Big Things". Alternative Press. No. 155. Alternative Magazines Inc. pp. 56–64. ISSN 1065-1667.

- ^ a b c Shooman, 2010. p. 84

- ^ a b Everett, Jenny (Fall 2001). "Blink-182 Cordially Invites You To Take Them Seriously". MH-18. Rodale, Inc. p. 81.

- ^ Nathan Brackett. (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. New York: Fireside, 904 pp. First edition, 2004.

- ^ a b Shooman, 2010. p. 85

- ^ Augusto, Troy J. (September 21, 2001). "Blink-182". Variety. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Shooman, 2010. p. 83

- ^ a b c d e f g Blink-182: Take Off Your Pants and Jacket Tour 2001 Official Program. MCA Records. 2001.

- ^ Shooman, 2010. p. 86

- ^ Coffman, Tim (October 12, 2022). "Blink-182's Most Underrated Songs". SPIN. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c Rob Sheffield (June 11, 2001). "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". Rolling Stone. No. 871. New York City: Wenner Media LLC. ISSN 0035-791X. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "Revisit The Commercial For Blink-182's 'Take Off Your Pants And Jacket'". iHeart. May 22, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Jon Wiederhorn (November 5, 2001). "Blink-182 To Show Up On Mad TV, Will 'Stay Together' For Next Video". MTV News. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ "Hot Product". Billboard. June 11, 2001. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Dansby, Andrew (June 20, 2001). "Blink-182 Take Off to No. 1". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Jim DeRogatis (July 9, 2001). "Blink-182 at the Tweeter Center". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Witt, Stephen (2015). How Music Got Free. New York: Penguin. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-525-42661-5.

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (July 6, 2016). "Readers' Poll: The 10 Best Pop-Punk Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Stewart, Allison (August 30, 2001). "Rock-star life is for Blink-182 bassist". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c Phil Dellio (July 10, 2001). "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". The Village Voice. New York City: Voice Media Group. ISSN 0042-6180. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "Blink-182 Opens At No. 1, Sugar Ray Debuts High". Billboard. June 2001. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ^ "Blink-182 enters charts at No. 1". June 20, 2001. Archived from the original on July 19, 2001. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Chartverfolgung / Blink-182 / Longplay Archived March 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Musicline.de (in German). Retrieved on January 18, 2014.

- ^ Dansby, Andrew (August 8, 2001). "'N Sync Ousted From Top". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "American album certifications – Blink-182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ "Blink 182 cancel UK tour". BBC News. December 21, 2001. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Adams, Matt (October 11, 2022). "Blink-182 are getting the band back together with a new tour". NPR. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Muhammad, Latifah (November 11, 2022). "Blink-182 Funko Pop: Where to Pre-Order the Must-Have Collectible Before It's Gone". Billboard. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket - blink-182". Metacritic. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Thomas Nassiff (July 26, 2011). "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". AbsolutePunk. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Darren Ratner. "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". All Music Guide. AllMusic. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ a b David Browne (June 18, 2001). "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ a b "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". Q. August 2001. p. 124.

- ^ Robert Christgau. "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ a b Aaron Scott (June 29, 2001). "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Jane Stevenson (June 17, 2001). "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". Toronto Sun. Toronto: Sun Media. ISSN 0837-3175. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Jaedicke, Jan. "Rock Hard review". Issue 171. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ Joanne Kaufman (June 18, 2001). "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". People. Vol. 55, no. 24. New York City: Time Inc. ISSN 0093-7673. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ ""It's not big, it's not clever, but it'll make them very, very rich":…". Kerrang!. June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Steven Wells (June 18, 2001). "Take Off Your Pants and Jacket: Review". New Musical Express. London: IPC Media. ISSN 1049-0434. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Sanneh, Kelefa (July 18, 2016). "Blink-182: Punk for All Ages". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Best of Rock & Metal - Die 500 stärksten Scheiben aller Zeiten (in German). Rock Hard. 2005. p. 27. ISBN 3-89880-517-4.

- ^ Sharples, Grant (June 11, 2021). "Blink-182's 'Take Off Your Pants And Jacket' Turns 20". Stereogum. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "The 50 Best Rock Albums Of The 2000s". Kerrang!. February 21, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ Corey Moss (February 16, 2001). "Blink-182 To Kick Off Civic Tour 2001". MTV News. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ Shooman, 2010. p. 87

- ^ a b "Fans Get First Crack At Blink-182 Summer Tour Tix". Billboard. May 11, 2001. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Curto, Justin (October 17, 2022). "Matt Skiba Is As Excited As You Are About the Blink-182 Reunion". Vulture. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "A rock show rebellion". Tampa Bay Times. September 10, 2005. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "Back Injury Scotches Blink-182 Euro Tour". Billboard. December 2001. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Shooman, 2010. p. 89

- ^ Randy Lewis (September 18, 2001). "Blink-182 Gets Back to Its Punk Business". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Shooman, 2010. p. 90

- ^ Shooman, 2010. p. 99

- ^ a b c Shooman, 2010. p. 101

- ^ a b Ian Winwood (February 1, 2006). "Blink-182 vs. Green Day". Kerrang!. No. 1090. London: Bauer Media Group. pp. 44–45. ISSN 0262-6624.

- ^ Shooman, 2010. p. 100

- ^ Shooman, 2010. p. 97

- ^ a b Lentini, Liza (February 18, 2022). "5 Albums I Can't Live Without: Avril Lavigne". SPIN. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Menapace, Brendan (April 22, 2021). "Still Killer: Deryck Whibley On Sum 41\'s "Fat Lip" 20 Years Later". Stereogum. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Burr, Ty (April 30, 2001). "The FTC raps the music industry's knuckles". EW.com. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ "Adult Music Pitched To Kids: FTC". Adweek. April 25, 2001. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ Gupta, Prachi (March 27, 2015). "The most hated bands of the last 20 years: "Like Nickelback before there was Nickelback"". Salon. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ Stegall, Tim (November 19, 2021). "These 15 punk albums from 2001 brought the genre back into the spotlight". Alternative Press Magazine. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Donahue, Anne T. (July 14, 2016). "Blink-182 And The Sad Fate Of The Cool Guys From High School". MTV. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Sampson, Issy (May 21, 2021). "All the small things: how Blink 182's Travis Barker became the most influential person in music". the Guardian. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ McGauley, Joe (June 24, 2016). "People Who Grew Up Using Napster Are Better Music Fans". Thrillist. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (April 3, 2024). "How Pirates and Factory Workers Changed Music Forever (and Made Eminem's Life Miserable)". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Bein, Kat (January 17, 2019). "The Chainsmokers Tease 'Amazing Song' With Blink-182: 'We Can Die Happy Now'". Billboard. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (January 8, 2014). "The Good, The Bad, and the Limp Bizkit: A 2014 Album Preview". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Lentini, Liza (July 8, 2022). "5 Albums I Can't Live Without: MOD SUN". SPIN. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Alligood, Kristen (September 27, 2014). "UK's You Me At Six cranks out high energy show". USA TODAY. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Elliot, Griffin (February 27, 2016). "Chicago Punks Knuckle Puck Share Their Love of Blink-182 and Canadian Exchange Rates". VICE. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "blink-182: How Take Off Your Pants And Jacket changed pop-punk forever". Kerrang!. June 12, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "Listen To Neck Deep Cover blink-182's Don't Tell Me It's Over". Kerrang!. May 10, 2019. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Tom Bryant (November 1, 2003). "But Seriously Folks…". Kerrang!. London. ISSN 0262-6624.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Blink-182 Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Eurochart Top 100 Albums - July 07, 2001" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 19, no. 28. July 7, 2001. p. 15. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2001. 29. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ "Irish-charts.com – Discography Blink 182". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "テイク・オフ・ユア・パンツ・アンド・ジャケット" (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on September 12, 2023. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Official Rock & Metal Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Blink-182 Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Albums for 2001". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2001". Ultratop. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Albums of 2001 (based on sales)". Jam!. Archived from the original on December 12, 2003. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "European Top 100 Albums 2001" (PDF). Music & Media. December 22, 2001. p. 15. Retrieved July 11, 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Top Albums annuel (physique + téléchargement + streaming)" (in French). SNEP. 2001. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts". GfK Entertainment (in German). offiziellecharts.de. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 2001". hitparade.ch. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2001". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Year in Music: 2001 – Top Billboard 200 Albums". Billboard. Vol. 113, no. 52. December 26, 1998. p. 33. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Top 50 Global Best Selling Albums for 2001" (PDF). IFPI. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2008. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Top 200 Albums of 2002 (based on sales)". Jam!. Archived from the original on September 6, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Alternative albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on December 4, 2003. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "2002 The Year in Music". Billboard. Vol. 114, no. 52. December 28, 2002. p. YE-34. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2001 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ "Brazilian album certifications – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Blink 182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". Music Canada.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Blink-182; 'Take Off Your Pants and Jacket')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ "Japanese album certifications – Blink-182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('Take Off Your Pants and Jacket')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- ^ "British album certifications – Blink-182 – Take Off Your Pants and Jacket". British Phonographic Industry.

General and cited references[edit]

- Barker, Travis; Edwards, Gavin (2015). Can I Say: Living Large, Cheating Death, and Drums, Drums, Drums. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-231942-5.

- Hoppus, Anne (October 1, 2001). Blink-182: Tales from Beneath Your Mom. MTV Books / Pocket Books. ISBN 0-7434-2207-4.

- Shooman, Joe (June 24, 2010). Blink-182: The Bands, The Breakdown & The Return. Independent Music Press. ISBN 978-1-906191-10-8.

External links[edit]

- Take Off Your Pants and Jacket at YouTube (streamed copy where licensed)

- Official website